I had an interesting discussion with Clark Quinn on using Kirkpatrick's model in learning processes other than courses. Clark argues that use of Kirkpatrick’s model is only for courses because training is the dominant discussion on their web site. I disagree and wonder if perhaps it is more of a “not invented here” hesitation because advancing concepts to the next level has often been a primary means of moving forward. It might sound good to forget an old model, but if you do not help people relearn, then their old concepts have a nasty habit of reappearing. In addition, training is far more than just courses. So after some heavy reflection I did a rewrite on my Kirkpatrick web page and have listed some of the highlights below.

More than Courses

While some mistakenly assume the four levels are only for training processes, the model can be used for other learning processes. For example, the Human Resource Development (HRD) profession is concerned with not only helping to develop formal learning, such as training, but other forms, such as informal learning, development, and education (Nadler, 1984). Their handbook, edited by one of the founders of HRD, Leonard Nadler, uses Kirkpatrick's four levels as one of their main evaluation models.

Kirkpatrick himself wrote, “These objectives [referring to his article] will be related to in-house classroom programs, one of the most common forms of training. Many of the principles and procedures applies to all kinds of training activities, such as performance review, participation in outside programs, programmed instruction, and the reading of selected books” (Craig, 1996, p294).

Kirkpatrick's levels work across various learning processes because they hit the four primary points in the learning/performance process... but he did get a few things wrong:

1. Motivation, Not Reaction

Reaction is not a good measurement as studies have shown. For example, a study shows a Century 21 trainer with some of the lowest reaction scores was responsible for the highest performance outcomes in post-training (Results) as measured by his graduates' productivity. This is not just an isolated incident—in study after study the evidence shows very little correlation between Reaction evaluations and how well people actually perform when they return to their job (Boehle, 2006).

When a learner goes through a learning process, such as an elearning course, informal learning episode, or using a job performance aid, the learner has to make a decision as to whether he or she will pay attention to it. If the goal or task is judged as important and doable, then the learner is normally motivated to engage in it (Markus, Ruvolo, 1990). However, if the task is presented as low-relevance or there is a low probability of success, then a negative effect is generated and motivation for task engagement is low. Thus it is more about motivation rather than reaction.

2. Performance, Not Behavior

As Gilbert noted, performance has two aspects: behavior being the means and its consequence being the end... and it is the consequence we are mostly concerned with.

3. Flipping it into a Better Model

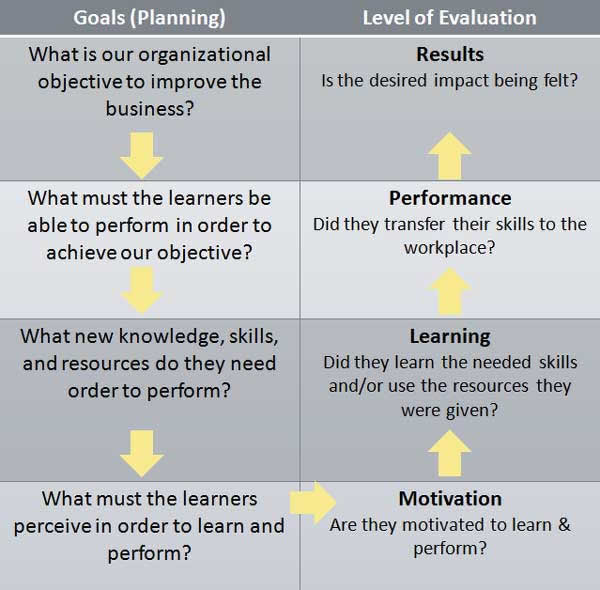

The four levels are upside down as it places the two most important items last—results, and behavior, which basically imprints the importance of order in most people's head. Thus by flipping it upside down and adding the above two changes we get:

- Result - What impact (outcome or result) will improve our business?

- Performance - What do the employees have to perform in order to create the desired impact?

- Learning - What knowledge, skills, and resources do they need in order to perform? (courses or classrooms are the LAST answer, see Selecting the Instructional Setting)

- Motivation - What do they need to perceive in order to learn and perform? (Do they see a need for the desired performance?)

With a few further adjustments, it becomes both a planning and evaluation tool that can be used as a troubling-shooting heuristic (Chyung, 2008):

The revised model can now be used for planning (left column) and evaluation (right column).

In addition, it aids the troubling-shooting process. For example, if you know the performers learned their skills but do not use them in the work environment, then the two more likely troublesome areas become apparent as they are normally in the cell itself (in this example, the Performance cell) or the cell to the left of it:

- There is a process in the environment that constrains the performers from using their new skills, or

- the initial premise that the new skills would bring about the desired change is wrong.

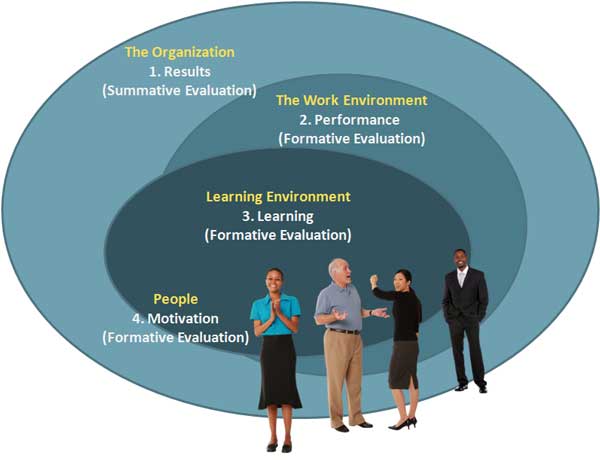

The diagram below shows how the evaluation processes fit together:

Learning and Work Environment

As the diagram shows, the Results evaluation is of the most interest to the business leaders, while the other three evaluations (performance, learning, and motivation) are essential to the learning designers for planning, evaluating, and trouble-shooting various learning processes; of course the Results evaluation is also important to them as it gives them a goal for improving the business. For more information see Formative and Summative Evaluations.

I go into more detail on my web page on Kirkpatrick is you would like more information or full references.

What are your thoughts?